There is no known remedy to this chestnut blight. It attacks all chestnut trees alike, whether in a millionaire’s park or farmer’s woodlot… Colonel Theodore Roosevelt is one of the worst sufferers. More than 1,000 trees in his Sagamore Hill estate are showing the mouldy orange spots and withered leaves of the disease. It is the same story in John D. Rockefeller’s estate in the Pocantino Hills and at Miss Helen Gould’s on the Hudson. Hudson Maxim is losing the chestnut trees on his broad acres bordering Lake Hopatcong. He has used his inventive powers and knowledge of science to find a remedy and failed.

– The New York Times, October 2, 1910

The American chestnut was once a predominant tree at Lake Hopatcong. Hotels advertised their “delightfully cool” chestnut groves and a stand of these trees was considered a selling point for any house on the market. The Angler newspaper in its August 31, 1895 issue extolling the virtues of fall at Lake Hopatcong noted that “few people have heretofore appreciated this place as a fall resort. Before last year the lake was deserted on the day after Labor Day, but last year the tide began to turn… and many of the cottagers, with a few campers, stayed to enjoy the cool nights and the chestnuts of September. For the children to amuse themselves there are bushels of chestnuts to be gathered that the first frost brings down in showers. The woods are nearly all of chestnut growth, and gathering them furnishes another source of amusement for young and old.”

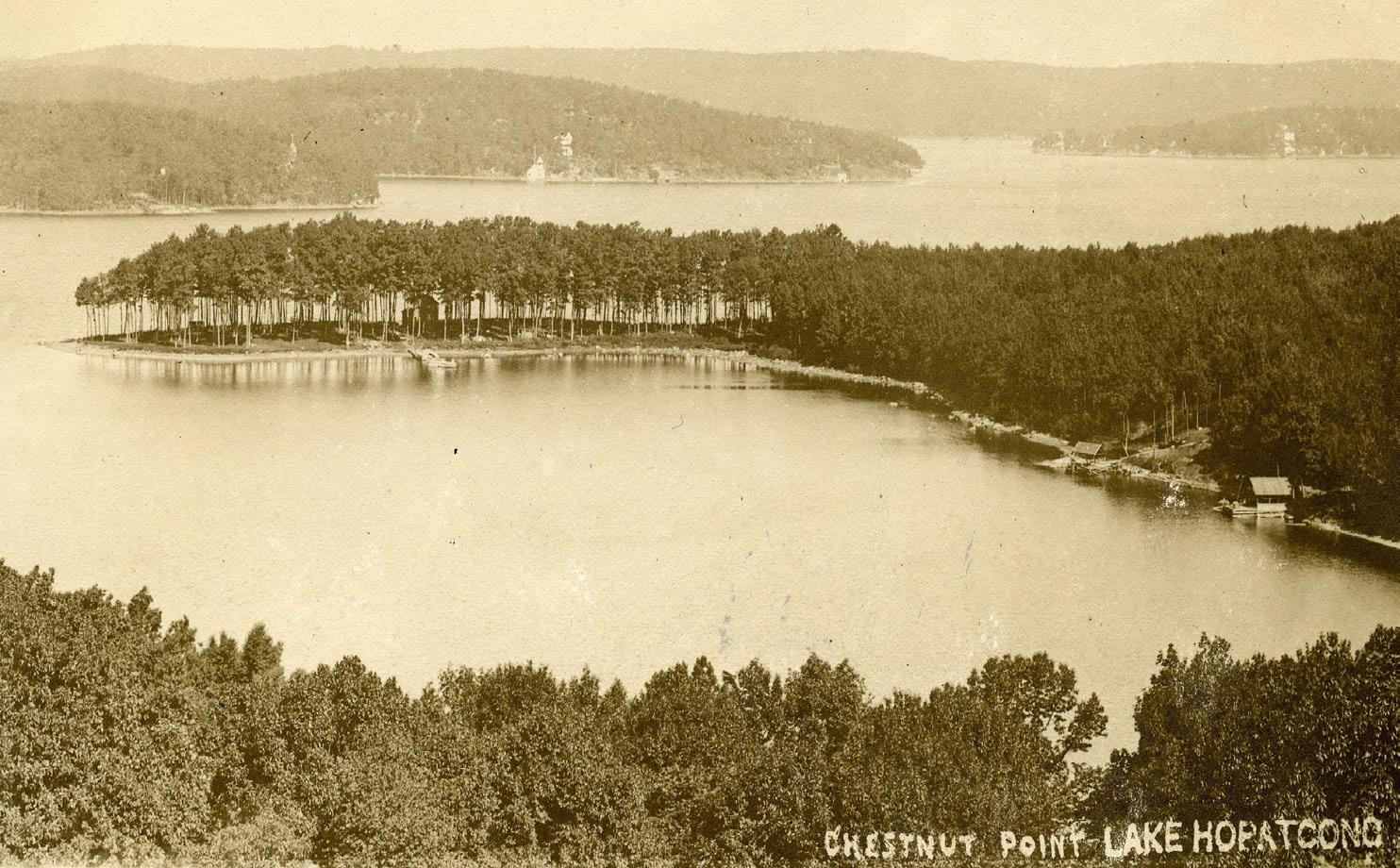

Whereas today some seasonal residents plan to remain at the lake through the first frost, the Lake Hopatcong Breeze used to report that families would stay “until chestnut time” or “until the chestnuts fall.” The name of Chestnut Point, a well-known area on the lake, is further evidence of the connection Lake Hopatcong once had to this tree.

It is estimated that the American chestnut inhabited over 200 million acres of eastern woodlands from Maine to Florida and west to the Ohio Valley prior to the blight. The chestnut tree was an essential component of the entire eastern United States ecosystem. A late-flowering, reliable, and productive tree unaffected by seasonal frosts, it was the single most important food source for a wide variety of wildlife. Communities depended upon the annual nut harvest as a cash crop and to feed livestock. The chestnut lumber industry was a major business. With its beautifully grained wood which was easy to work, lightweight, and highly rot-resistant, the chestnut was considered ideal for fence posts, railroad ties, barn beams and home construction, as well as fine furniture and musical instruments.

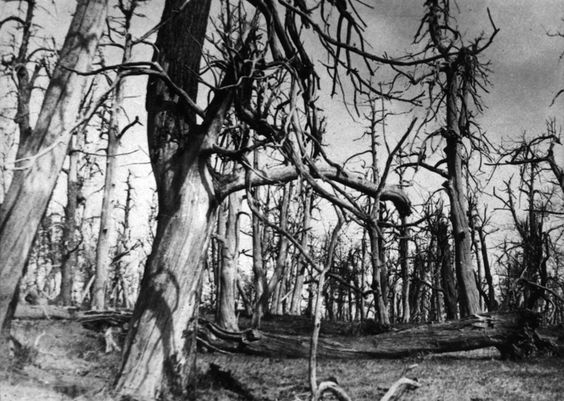

In 1904, curators of New York’s Bronx Zoo noticed an unusual malady afflicting the magnificent chestnut trees lining the avenues of the zoo. Later determined to be the result of a fungus accidentally introduced to America on chestnut trees imported from Japan, this condition was named chestnut blight. Its symptoms included wilting leaves, large cankers with rupturing bark, sprouts below the cankers and shortly thereafter, death of the tree’s trunk and upper limbs. In 1907 and 1908, trees in the New York Botanical Garden exhibited the same symptoms. Before anyone could determine what was happening, the mysterious infection spread to chestnuts throughout New England and worked its way east, killing virtually every chestnut tree in its path. By the time the devastation was done, an estimated three to four billion American chestnut trees are believed to have been lost.

The chestnut blight was first noted at Lake Hopatcong in 1910. The July 2, 1910 Breeze reported that “Mr. Maxim is cutting all of the chestnut trees on his properties, owing to the chestnut bark disease, which the Forestry Department claims will destroy all of the chestnuts in the United States during the next few years, unless Nature unexpectedly intervenes to save them.” In a July 23, 1910 letter to the Breeze editor, Hudson Maxim explained that “some of my neighbors have wondered why I am cutting the chestnut trees on my property and sawing them into lumber, or selling them for telephone and telegraph poles, notwithstanding the fact that they are among the most beautiful and most valuable trees we have. In the forests and by the roadsides all about us may be seen chestnuts in every stage of the disease – from those with newly withered leaves in the tops and branches to trees already bare and dead… There is every indication that all our chestnut trees are doomed.” And in fact over the next few years almost every chestnut around Lake Hopatcong either died or was cut down for its lumber before it could succumb to the blight.

A 1923 Breeze article noted that “chestnuts in this part of the country have been scarce and very rare. On many occasions fresh sprouts would spring up from old chestnut stumps and grow into young saplings. Property owners would observe and care for them with great interest hoping that again their grounds would be beautified by this magnificent tree. But after a few years’ growth the sapling would wither and die.” Indeed for many years, there were excited reports of new chestnut saplings as proof that the blight was finally over. However, these trees would also invariably succumb to the disease.

Since its founding in 2012, the Lake Hopatcong Foundation has been at the forefront of multiple initiatives to improve and enhance the experience at New Jersey’s largest lake. The foundation acquired the historic Lake Hopatcong Station in Landing in November 2014 to serve as its offices and a community center. The train station building needed extensive restoration and as part of the process a landscape design was developed consistent with the age of the building. During the planning phase, the dialogue began to include one or more American chestnut trees in the station’s landscape.

Beginning in the 1920s, government agencies and universities attempted to breed blight-resistant chestnuts by crossing Chinese and Japanese chestnuts with the American species. Efforts proved unsuccessful as the resulting trees either were not blight resistant or did not reach American chestnut standards for nut taste or timber quality. The American Chestnut Foundation was founded in 1983 with a mission of developing a blight-resistant American chestnut tree through scientific research and breeding, and restoring the tree to its native forests along the eastern United States. The ACF’s breeding efforts since then have led to a tree which is 94% American chestnut with all of the characteristics of the American variety and thus far blight resistant. The Lake Hopatcong Foundation applied to receive seedlings for planting at the Lake Hopatcong Station in April 2016. After a fairly extensive vetting process, the request was approved and the American Chestnut Foundation hand delivered five seedlings in September 2016.

The trees were immediately planted by the LHF’s landscaping committee and have thrived in the ensuing years. As a native species, the American chestnut is well prepared for local climactic conditions. The young trees only needed to be protected from deer and other critters which love the taste of the bark and leaves. As of the summer of 2021, the trees ranged in height from 7’ to 15’. And in August 2021, one of the five trees produced the first chestnuts – perhaps the first American chestnut produced at Lake Hopatcong in over a hundred years! Stay tuned for what will hopefully be the long-term return of an old friend to Lake Hopatcong – the American chestnut.