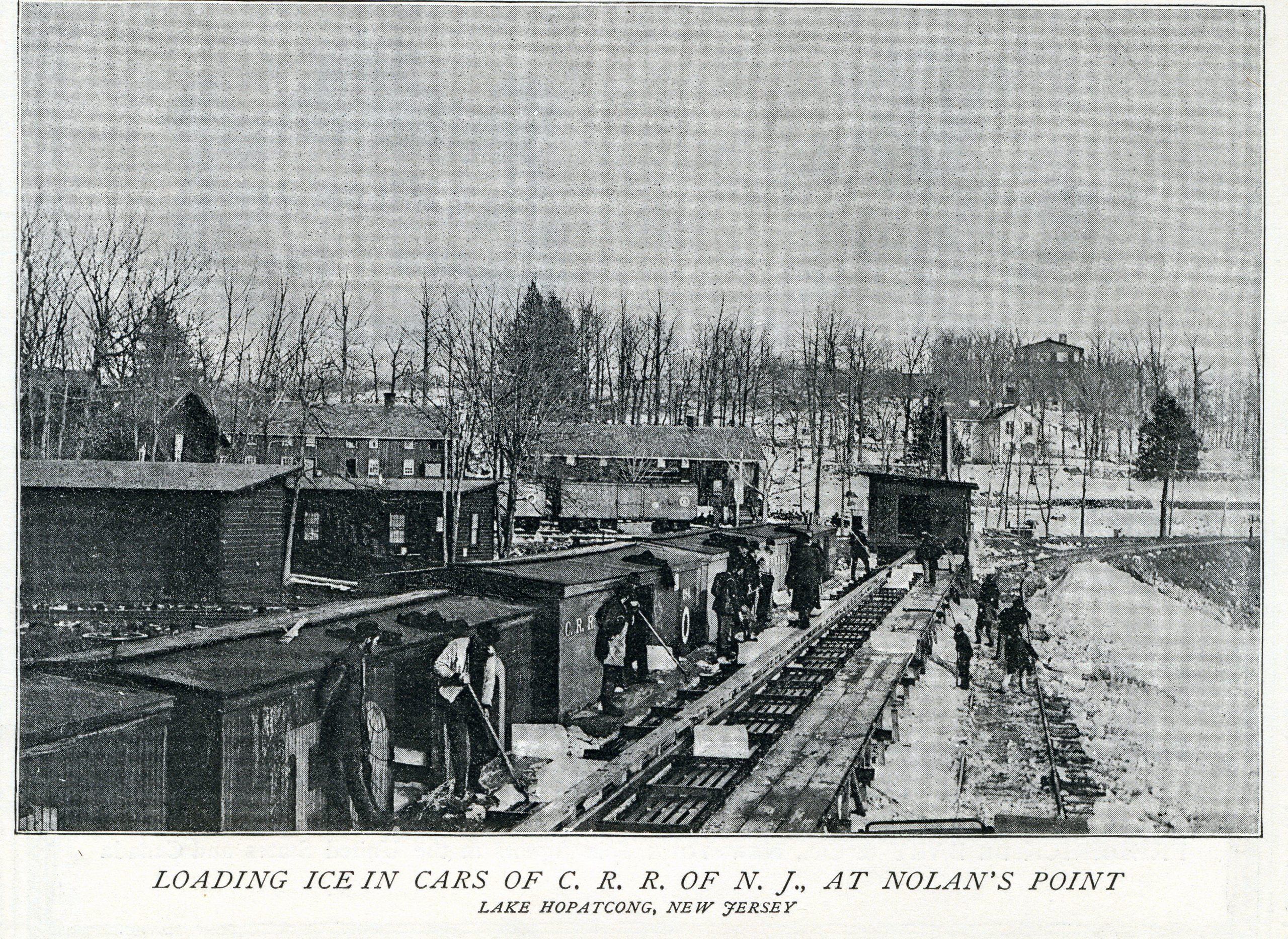

Though it is hard to imagine today, ice was once big business at Lake Hopatcong. The ice industry employed hundreds of workers each winter, and trains carried many tons of ice from the lake to New York and other large cities daily. Some of this ice was loaded onto ships in New York Harbor and transported as far as the Caribbean and South America.

The ice industry was a critical part of 19th and early 20th century life before the invention of electric refrigeration. The United States led the industry internationally along with Norway. The US industry, centered on the east coast, involved the large-scale harvest, transport, and sale of natural ice for residential and commercial use. Ice cut from the frozen surfaces of lakes and rivers was hauled by ship, barge, or rail to destinations around the world. Networks of wagons distributed the ice locally to homes and businesses. A block of ice delivered directly to residences by the local ice man would be placed in the kitchen ice box in order to keep food refrigerated. Ice allowed for the introduction of refrigerated rail cars and ships, which revolutionized the meat, fish, vegetable, and fruit industries, and led to the introduction of new foods and beverages. Suddenly foods that had previously been available only for local consumption could be shipped across the country.

Located close to large cities and having almost no other industry, the lakes of northwestern New Jersey were a reliable source of ice. Ice cut from a lake and stored in an ice house could remain frozen for many months, often until the following winter, and be used throughout the summer months. The main utilization of the ice was the storage of food, but it could also be used to cool drinks or in the preparation of ice cream and other treats.

The first ice house at Lake Hopatcong was built around 1860, but the ice industry surged with the arrival of rail service to the lake in 1882. At the industry’s peak in the early 20th century, Lake Hopatcong was home to four major ice houses, massive three and four story buildings in which ice was stacked and covered with straw or sawdust for insulation. These were located at Silver Springs, Nolan’s Point, Hurd or Callahan Cove (just inside Brady Bridge), and Woodport (in the area near today’s Lake Forest Yacht Club). A fifth large ice house was located at nearby Duck Pond (today’s Lake Shawnee). Brady Brothers Consumers Ice Company of Bayonne owned all of these businesses except for the Silver Springs enterprise, which belonged to the Mountain Ice Company of Hoboken. In addition, small ice houses existed at the lake for private use, and Sohner’s Ice House in River Styx delivered ice around the lake.

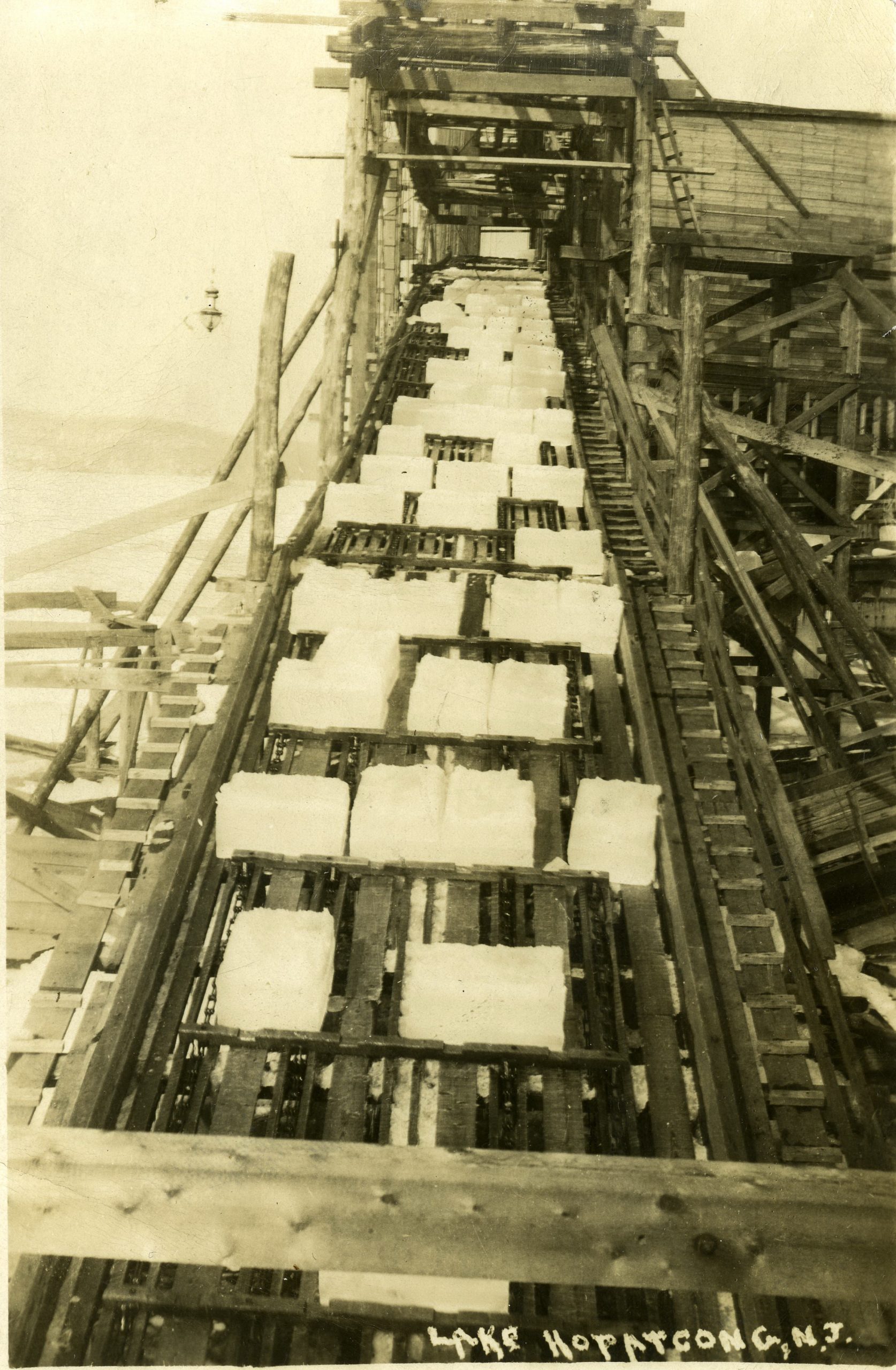

A typical winter at Lake Hopatcong produced two ice harvests. Large areas of the lake were cut using plow-like devices pulled by horses. The ice was initially hand sawed into blocks and transported on long conveyors into an ice house. Motor driven saws later mechanized this process. As winter sports became increasingly popular at the lake in the 1910s and 1920s, harvested areas were marked to keep winter sports enthusiasts away.

The two most visible ice houses were the Nolan’s Point and Silver Springs structures. The Nolan’s Point Ice House dominated the area between the current Windlass and Jefferson House restaurants. The 1898 Illustrated Guide to Lake Hopatcong reported that of the 50,000 tons of ice cut the previous winter at Nolan’s Point, 8,000 tons was stored in the ice house and the rest shipped on the Central Railroad of New Jersey. During summers in the 1890s and early 1900s it was common for at least one train filled with ice to leave Nolan’s Point daily. The July 18, 1903 Lake Hopatcong Breeze reported that “the largest train of ice ever pulled from Lake Hopatcong in summer was last Friday, July 10, thirty-six cars being pulled by two engines.”

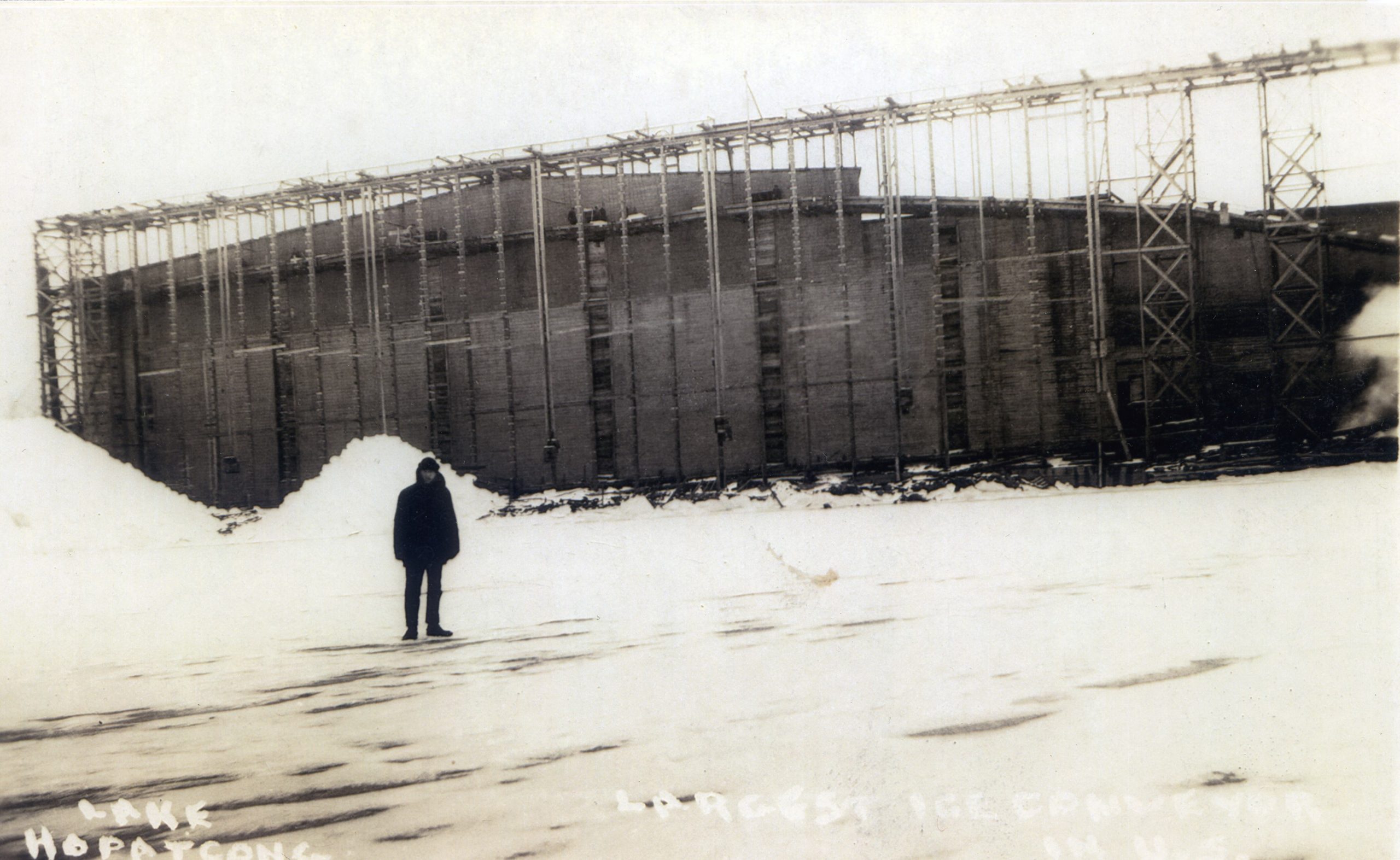

The Mountain Ice House, located near Silver Springs in the area of today’s Auriemma Court, was the largest ice house at Lake Hopatcong. Constructed in 1898, it dominated the southern part of the lake. After the enormous wooden structure suffered a devastating fire in 1912, Mountain Ice replaced it with a new hollow tile building. In addition to being fireproof, the tiles were perfect for insulation. Constructed of some 5 million tiles over an eight month period in 1913, the new building was 56 feet high and was reportedly the largest ice house in the country at the time. According to the August 19, 1939 issue of the Lake Hopatcong Breeze, the building had been the largest single girder construction in the country until Radio City Music Hall was built in 1932. The ice house featured walls consisting of two layers of tile sandwiched around three feet of sawdust for insulation. Even the roof contained several feet of sawdust to keep out the summer heat. This method of construction proved to be an excellent housing for the 100,000 tons of ice that the building could hold.

By the 1920s huge ice houses were no longer necessary. While it would still be years before most families owned an electric refrigerator, the development of electric refrigeration and ice making equipment allowed ice to be manufactured at plants located within cities. The Mountain Ice House was the last operating at the lake as the 1930s dawned. Nolan’s Point Ice House was demolished and the property developed as Nolan’s Point Amusement Park in 1928. The land from the two ice houses at the northern end of the lake remained empty through the Depression and World War II, and was later incorporated into the developments of East Shore Estates and Lake Forest. The Mountain Ice House harvested its last ice in 1935 and was torn down in 1939. It had occupied 800 feet of prime lake frontage which had been leased from the King family. Following the demolition of the ice house, the property remained vacant for years as Louise King resisted developing the land. She did sell some parcels over the years, including one to Roxbury which enabled the construction of Nixon School in 1969. After her passing, the property was developed for the homes located today along Auriemma Court.

A few traces of the ice industry are still visible at Lake Hopatcong. At Nolan’s Point some stone remains of the old ice house can still be seen in a small inlet. The past is a bit easier to observe at Silver Springs. John Carey, the superintendent of the ice house from its construction in 1913 until its closure, lived on the ice house property until his death in the 1940s in a home constructed with the same hollow tiles used for the ice house. The unique building still stands today on Mount Arlington Boulevard next to the Nixon School, a tribute to a bygone era at the lake.