Lake Hopatcong Cruise’s Miss Lotta has become a popular fixture on the lake. When the boat first arrived and a name was being considered, it seemed only natural to invoke the lake’s first great celebrity – Lotta Crabtree or “Miss Lotta” as she was simply known. For some 25 years of the 19th century, Lotta was the most celebrated actress in America. While her career overlapped that of the renowned Sarah Bernhardt, Lotta was more popular in this country. Articles and books of the day widely referred to her as “the Nation’s Darling” and more recent theatrical histories have acknowledged her as “America’s first superstar.”

Lake Hopatcong Cruise’s Miss Lotta has become a popular fixture on the lake. When the boat first arrived and a name was being considered, it seemed only natural to invoke the lake’s first great celebrity – Lotta Crabtree or “Miss Lotta” as she was simply known. For some 25 years of the 19th century, Lotta was the most celebrated actress in America. While her career overlapped that of the renowned Sarah Bernhardt, Lotta was more popular in this country. Articles and books of the day widely referred to her as “the Nation’s Darling” and more recent theatrical histories have acknowledged her as “America’s first superstar.”

Charlotte “Lotta” Mignon Crabtree was born in 1847 in New York City but grew up in the Gold Rush towns of California. Her father, John Crabtree, traveled to California in search of gold in 1851. Young Lotta and her mother, Mary Ann, followed the next year. By 1853 the family had settled in Grass Valley, California, and it was about this time that Mary Ann embarked her daughter on a theatrical career which made her a child star throughout gold country. Touring the local towns, Lotta entertained the miners with singing, dancing, and playing the banjo. The legendary Lola Montez was a neighbor of the Crabtrees at the time. The famous dancer, royal courtesan, and actress took a liking to Lotta, tutoring her in singing and dancing. The family’s move to San Francisco in 1856 brought Lotta to a real stage for the first time and started her on the road to true fame. At the age of nine she was billed as “Miss Lotta, San Francisco’s Favorite.”

In 1864, Lotta Crabtree left San Francisco to great fanfare to conquer the rest of America. Over the next two decades, she became a household name throughout the country. It was said that if Lotta’s name was on the program the show was sure to be a hit. In the 1870s she established her own touring company, which allowed her to work continuously with the same actors rather than hiring local players in each city, which was customary at the time. Lotta was the highest paid actress in America during the 1880s, earning sums of up to $5,000 per week, an incredible amount by the standards of the day. The New York newspapers dubbed her the Belle of Broadway. The New York Times called her the “eternal child” with “the face of a beautiful doll and the ways of a playful kitten.”

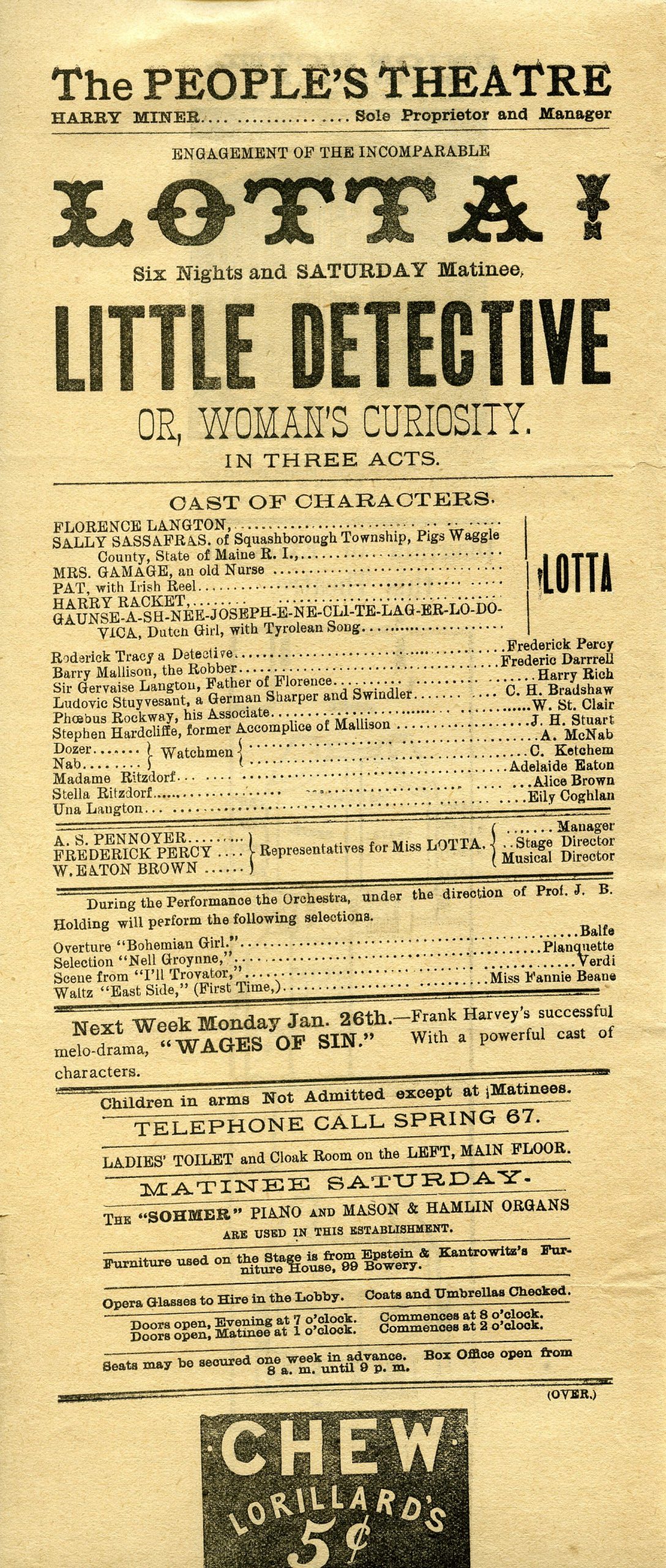

Early theatre expert Professor David S. Shields of the University of South Carolina explains Lotta’s rise as follows. “Lotta performed Irish jigs in the camp saloons. …her Montez-burnished skill as songstress found her a place on the stage. She developed a deft hand at banjo playing, delighted in the rough humor of largely male audiences in that libertine city, and as a girl learned to wriggle seductively to the astonishment of onlookers. Though beautiful and schooled in being alluring, she was impatient with simply being a pretty thing, and strove to impersonate all sorts of feminine types while still a teenager. Off-stage Crabtree developed a number of bohemian habits—dressing in men’s trousers and smoking thin black cigars. The latter may have been a legacy of her contact with Montez, along with political radicalism. [Lotta played] the title role of Little Nell and the Marchioness in New York. Her spirited rollicking portrayal galvanized the public and Crabtree quickly became a theatrical sensation. She rarely appeared in roles as a conventional romantic lead. She favored girl roles, or mischievous old ladies, or trouser roles, or comic turns. While she could elicit tears as little Nell, she preferred to provoke laughter, and she was fearless in her pursuit of roles, gestures, voices, and make up that would set the audience roaring. Until Lon Chaney appeared in the silent motion picture era, no performer in the United States explored the limits of impersonation as selflessly as Lotta. Later in her career, she sought stage vehicles that permitted her to alter personae multiple times during the course of an evening. ‘The Little Detective’ enabled her to be an aged spinster, a girl, and a flash bachelor. In the 1880s, when she was in her thirties and forties, she delighted in reverting to her first role, that of a rollicking teenage girl.”

Early theatre expert Professor David S. Shields of the University of South Carolina explains Lotta’s rise as follows. “Lotta performed Irish jigs in the camp saloons. …her Montez-burnished skill as songstress found her a place on the stage. She developed a deft hand at banjo playing, delighted in the rough humor of largely male audiences in that libertine city, and as a girl learned to wriggle seductively to the astonishment of onlookers. Though beautiful and schooled in being alluring, she was impatient with simply being a pretty thing, and strove to impersonate all sorts of feminine types while still a teenager. Off-stage Crabtree developed a number of bohemian habits—dressing in men’s trousers and smoking thin black cigars. The latter may have been a legacy of her contact with Montez, along with political radicalism. [Lotta played] the title role of Little Nell and the Marchioness in New York. Her spirited rollicking portrayal galvanized the public and Crabtree quickly became a theatrical sensation. She rarely appeared in roles as a conventional romantic lead. She favored girl roles, or mischievous old ladies, or trouser roles, or comic turns. While she could elicit tears as little Nell, she preferred to provoke laughter, and she was fearless in her pursuit of roles, gestures, voices, and make up that would set the audience roaring. Until Lon Chaney appeared in the silent motion picture era, no performer in the United States explored the limits of impersonation as selflessly as Lotta. Later in her career, she sought stage vehicles that permitted her to alter personae multiple times during the course of an evening. ‘The Little Detective’ enabled her to be an aged spinster, a girl, and a flash bachelor. In the 1880s, when she was in her thirties and forties, she delighted in reverting to her first role, that of a rollicking teenage girl.”

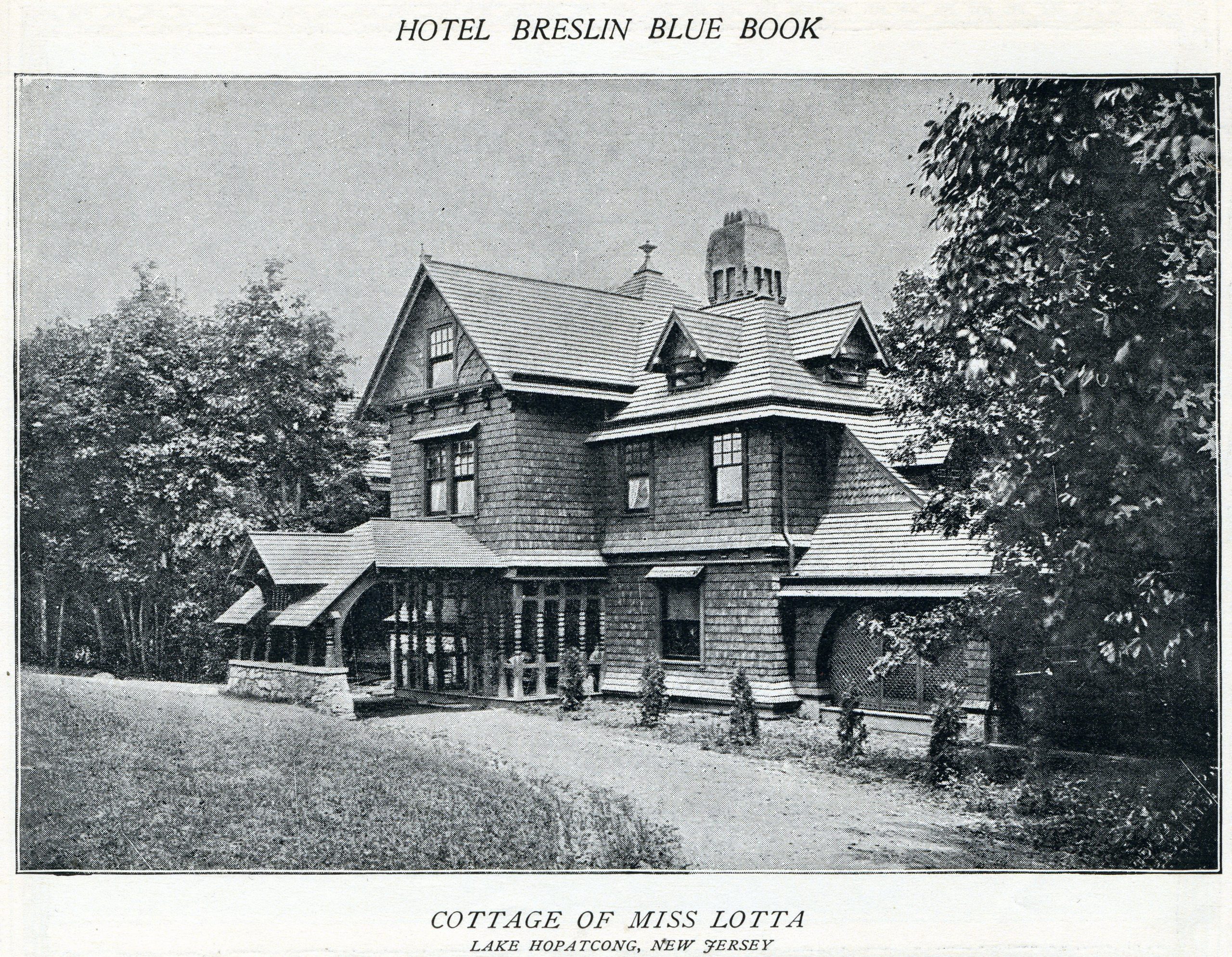

Lotta’s association with Lake Hopatcong began in the 1880s. When not on tour, she and her mother lived in an apartment on New York’s Fifth Avenue. Among their neighbors and close friends were Mr. and Mrs. Robert Dunlap. Dunlap owned a fashionable men’s hat store and among his customers were some of New York’s wealthiest gentlemen, including J.P. Morgan, Jay Gould, and John Jacob Astor. He had close acquaintances throughout New York City’s rich and famous and it was in this manner that he became involved with a development being planned in the hills of northwestern New Jersey. At the time Lake Hopatcong was just beginning to grow as a resort. A group of wealthy investors, including Dunlap, conceived the idea of an exclusive community in Mount Arlington to be centered around hotel magnate William Breslin’s massive hotel and surrounded by a colony of millionaires “cottages” known as Breslin Park. Dunlap built one of the first cottages and Mary Ann Crabree worked with him to purchase a choice parcel on which to build a grand summer cottage as a surprise gift for Lotta. The house, completed in 1886, was one of the finest built in Breslin Park – an 18-room mansion with a wine cellar, billiard room, music room, library, beautiful fireplaces, and sweeping verandas. The house was designed by noted Philadelphia architect Frank Furness and Mary Ann (who managed all aspects of Lotta’s career) was involved in all of the planning including the ornate furnishings. She named the house “Attol (Lotta spelled backwards) Tryst.”

Lotta used the lake as a place to rest and entertain in the summers when most theaters went dark and during breaks in her demanding touring schedule. It provided a well-needed respite in the country. The Lake Hopatcong Breeze reported numerous times that Lotta enjoyed taking her carriage and horses out every afternoon with her mother, brother, or visitors riding along. She owned a motorboat and sailboat, which was stored in her large boat house fronting on Van Every Cove. Lotta’s brother Jack loved visiting and even brought a steam launch from Boston to the lake via the Morris Canal in 1895. In the 1891 Guide to Lake Hopatcong, author O.F.G. Megie wrote that, “just outside the [Hotel] Breslin grounds opposite the hotel, is the pretty cottage of Lotta, the actress, whose granite fire-places, oaken stairway, well-ordered dining room, attractive billiard room, and charmingly-appointed reception room, show an owner of taste, means and leisure. But this last indication is deceptive, for Lotta, though reputed to be one of the richest actresses in the world, is also one of the busiest. By the time one has become accustomed to seeing the little naphtha launch, the ‘Lotta,’ with its famous owner at the wheel, flying over the lake on its daily outing, these journeys suddenly cease, and in the morning paper one sees that Lotta is in Chicago or Maine, or some other equally distant point, playing to crowded houses.”

Lotta used the lake as a place to rest and entertain in the summers when most theaters went dark and during breaks in her demanding touring schedule. It provided a well-needed respite in the country. The Lake Hopatcong Breeze reported numerous times that Lotta enjoyed taking her carriage and horses out every afternoon with her mother, brother, or visitors riding along. She owned a motorboat and sailboat, which was stored in her large boat house fronting on Van Every Cove. Lotta’s brother Jack loved visiting and even brought a steam launch from Boston to the lake via the Morris Canal in 1895. In the 1891 Guide to Lake Hopatcong, author O.F.G. Megie wrote that, “just outside the [Hotel] Breslin grounds opposite the hotel, is the pretty cottage of Lotta, the actress, whose granite fire-places, oaken stairway, well-ordered dining room, attractive billiard room, and charmingly-appointed reception room, show an owner of taste, means and leisure. But this last indication is deceptive, for Lotta, though reputed to be one of the richest actresses in the world, is also one of the busiest. By the time one has become accustomed to seeing the little naphtha launch, the ‘Lotta,’ with its famous owner at the wheel, flying over the lake on its daily outing, these journeys suddenly cease, and in the morning paper one sees that Lotta is in Chicago or Maine, or some other equally distant point, playing to crowded houses.”

Lotta was Lake Hopatcong’s most famous resident for many years. Her presence helped bring publicity to the Hotel Breslin and the developing resort, with the New York papers frequently reporting on her activities at the lake. From the time the house was given to her in 1886, she spent part of almost every summer there for the next 15 years. In fact in years such as 1897, she arrived at the lake in April and stayed through the summer. Though she came to Lake Hopatcong for a break from her very public persona, Lotta participated in various social and civic events. The Breeze reported on her attendance at fireworks, the annual Breslin Ball, and many other events over the years. She hosted recitals and lectures as well as large house parties at her cottage. Lotta was a generous participant in many aspects of lake life. She donated a sanctuary carpet to Our Lady of the Lake Church in Mount Arlington, though she was not Catholic, and one of the major annual trophies awarded by the Lake Hopatcong Canoe Club, of which she was an honorary member, was the “Lotta Challenge Cup”.

Lotta retired in 1892 while still enjoying great popularity. After sustaining injuries in an onstage fall at Wilmington, Delaware in 1889, she attempted a comeback in 1891 but due to lingering pain soon left the stage for good at the age of 45. Though she continued to own her cottage and visit periodically, she spent less time at the lake after the 1901 season. She traveled abroad some summers and spent others in Massachusetts or elsewhere. She pursued her love of painting, even studying in Paris for a time. In 1915, the Breeze reported that she had visited with the Chaplins at the Hotel Boulevard in Mount Arlington and stayed with the Walshes at their house on Arlington Avenue while having her cottage readied. Just after Lotta’s death in 1924, the Lake Hopatcong Breeze reported that, “as she grew older her visits became fewer and she sold the cottage a few years ago to Gerald M. Horgan of Dover. During her occupancy it was known as Lotta Cottage and is still called that by the old-timers. Miss Crabtree’s last visit to the Lake was made in the fall of 1922. She stayed three weeks at the Alamac [Hotel] and a number of her old Hopatcong friends had dinner with her there.”

Lotta retired in 1892 while still enjoying great popularity. After sustaining injuries in an onstage fall at Wilmington, Delaware in 1889, she attempted a comeback in 1891 but due to lingering pain soon left the stage for good at the age of 45. Though she continued to own her cottage and visit periodically, she spent less time at the lake after the 1901 season. She traveled abroad some summers and spent others in Massachusetts or elsewhere. She pursued her love of painting, even studying in Paris for a time. In 1915, the Breeze reported that she had visited with the Chaplins at the Hotel Boulevard in Mount Arlington and stayed with the Walshes at their house on Arlington Avenue while having her cottage readied. Just after Lotta’s death in 1924, the Lake Hopatcong Breeze reported that, “as she grew older her visits became fewer and she sold the cottage a few years ago to Gerald M. Horgan of Dover. During her occupancy it was known as Lotta Cottage and is still called that by the old-timers. Miss Crabtree’s last visit to the Lake was made in the fall of 1922. She stayed three weeks at the Alamac [Hotel] and a number of her old Hopatcong friends had dinner with her there.”

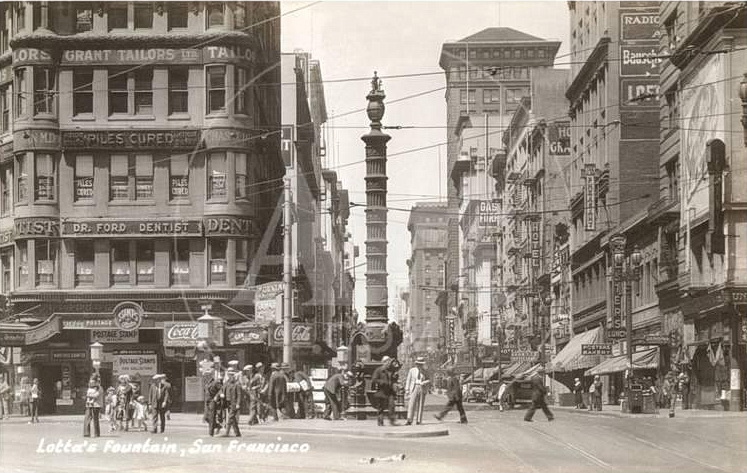

In retirement, Lotta studied painting, managed and reinvested the numerous real estate assets her mother had acquired during her career, and had considerable success as an owner of race horses. She never married. (Some said her mother would not allow it as this would affect her ability to be considered forever young.) In her Will, Lotta left her approximately $4 million estate to charities benefitting among others World War I veterans, farmers, the poor, animals, and aging actors. Several testaments to her can be found around the country. The Lotta Crabtree Trust created by her Will is still in operation. Lotta’s Fountain, which she donated to the people of San Francisco in 1875, survived the Great Earthquake of 1906 and still stands at the corner of Market and Geary Streets, having been beautifully restored in recent years. There is a Lotta Crabtree window at St. Stephen’s Church in Chicago, a Crabtree Hall dormitory at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, a second fountain along the Charles River in Boston, and a beautiful cottage designed for her by one of America’s greatest architects along the shores of Lake Hopatcong.

In an era before movies and television, Lotta’s act was never saved for posterity. Consequently, as those who had seen and idolized her passed on, Lotta’s fame, like those of other early theatrical stars, faded away. In 1915, she made what was considered her last public appearance for “Lotta Crabtree Day” in San Francisco at the Panama-Pacific Exposition, where the citizens turned out to remember their beloved Lotta. Her death, more than 30 years after her retirement from the stage, was widely noted in the newspapers. Those researching 19th century theatre will find Lotta’s name at the forefront. Interestingly, her rise from the American west has caught the attention of writers over the years. Sixty years ago when westerns were wildly popular in America, Lotta once again found her way into the media as writers were inspired by her life story. Though the tales they developed bore little resemblance to her real life, Lotta was a featured character in early TV episodes of Bonanza and Death Valley Days and was the subject of the 1951 Hollywood movie Golden Girl starring Mitzi Gaynor.

In an era before movies and television, Lotta’s act was never saved for posterity. Consequently, as those who had seen and idolized her passed on, Lotta’s fame, like those of other early theatrical stars, faded away. In 1915, she made what was considered her last public appearance for “Lotta Crabtree Day” in San Francisco at the Panama-Pacific Exposition, where the citizens turned out to remember their beloved Lotta. Her death, more than 30 years after her retirement from the stage, was widely noted in the newspapers. Those researching 19th century theatre will find Lotta’s name at the forefront. Interestingly, her rise from the American west has caught the attention of writers over the years. Sixty years ago when westerns were wildly popular in America, Lotta once again found her way into the media as writers were inspired by her life story. Though the tales they developed bore little resemblance to her real life, Lotta was a featured character in early TV episodes of Bonanza and Death Valley Days and was the subject of the 1951 Hollywood movie Golden Girl starring Mitzi Gaynor.

Some 100 years after Lotta sold her cottage at the lake, the house still stands on Edgemere Avenue. Beautifully maintained and restored in recent years, it is a striking tribute to one of America’s greatest stars.